SAMA 2023 English

Agarita returns to the San Antonio Museum of Art during its 3-hour free admission for an immersive musical experience that highlights the aesthetics of four unique galleries. Visitors will choose their own path, guided by sounds Baroque, Modern and Contemporary throughout the museum and culminating in special performances in the Contemporary and Latin American galleries.

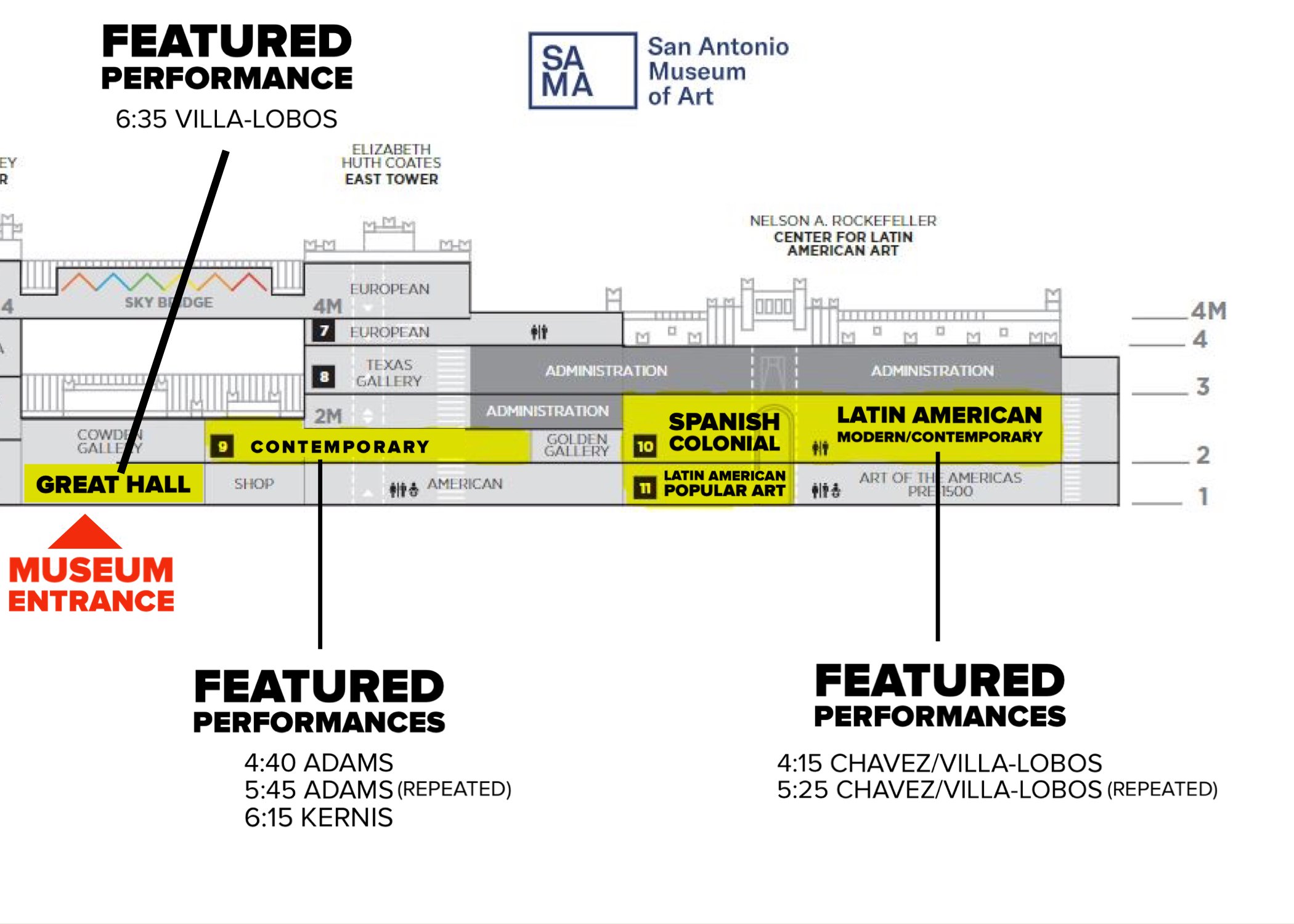

Galleries and Featured Performances:

FEATURING

Aimee Lopez

A native of the Washington DC area, violinist Aimee Lopez officially became a Texan when she joined the San Antonio Symphony in 2008 after completing a coveted four year fellowship with The New World Symphony under the direction of Michael Tilson Thomas. She is also a violinist with The Colorado Music Festival Orchestra in Boulder, Colorado. She has performed on stages throughout Europe, performing a month-long residency of Gershwin's Porgy and Bess at L'Opera Comique in Paris and The Alhambra in Spain. Aimee has given solo recitals and collaborated on chamber concerts in Washington DC, Baltimore, Houston, Boulder and Santa Cruz. Aimee has a passion for nurturing young minds and hearts through music. She directs a busy private violin studio where she actively develops the talents of young people on a weekly basis. Prior to her engagement in San Antonio, she earned degrees from The Peabody Institute and Rice University’s Shepherd School of Music where she studied under Elisabeth Adkins, Violaine Melancon, Shirley Givens, and Kathleen Winkler. Aimee lives in San Antonio with her husband, Dave, stepson, David and the newest addition to the family: two year old son, Gus.

PROGRAM NOTES BY GALLERY

THE VICEREGAL LATIN AMERICAN GALLERY

For this gallery, we are lucky to be able to use an instrument by local harpsichord builder Gerald Self. His expertise, craftsmanship and generosity are deeply appreciated.

The Sonatas for Viola da Gamba and Harpsichord by J.S. Bach are sonatas that have been arranged for a variety of instruments, but were originally of course for the viola da gamba (or viol), an upright instrument held between the legs like a modern cello. For this program, we have taken the patient and highly expressive third movement (an Andante in a minor key) of Sonata No. 1 in G major, and used it as an introduction for the first movement (an intense, lively Vivace) of Sonata No. 3 in G minor. Nonstop counterpoint between the two instruments, constant harmonic sequences, and frequent mood shifts fills the Vivace with an incessant energy. Brief moments of lyricism give in to the essential rhythm, which never stops.

Domenico Scarlatti wrote over 500 single-movement keyboard sonatas, and they have so much variety in mood, style, character, and technique that it can be hard to believe it all came from a single person. Scarlatti spent much of his life in the service of the Portuguese and Spanish royal families during the early to mid 18th century; he taught the Portuguese princess Maria Magdalena Barbara, who later became the Queen of Spain. Some of the sonatas include Iberian folk influences and use modal harmonies foreign to typical Baroque music, and some of the musical figures imitate the guitar in their ornamentation and style. His Sonata in E major, K. 380, performed frequently by the famous concert pianist Vladamir Horowitz on the modern keyboard, is an elegantly structured form that shifts from march-like trumpet calls to beautiful lyricism. The Sonata in A minor, K. 61 is a sort of variations on a very simple set of harmonies. Fast, sixteenth-note figures and even faster triplets help to create a frenetic energy that permeates the work.

Carlos Seixas was an 18th century Portuguese composer who is most known for his keyboard sonatas. Unfortunately much of his work was destroyed in the great earthquake that impacted Lisbon in 1755. The first movement of his Sonata No. 12 C Minor is a flowing Andante Pastorale whose mood changes from a dark and reflective minor song to a somewhat gleeful and carefree minuet feeling in major. Quirky dissonances and expressive ornaments in the development (middle) section dramatize the work and reassert a serious mood.

MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY LATIN AMERICAN GALLERY

Argentine composer Osvaldo Golijov has had an array of influences, from Jewish liturgical and klezmer music to nuevo tango to traditional classical music. For his work Omaramor, he took inspiration from an important Latin American musician:

“Carlos Gardel, the mythical tango singer, was young, handsome, and at the pinnacle of his popularity when the plane that was carrying him to a concert crashed and he died, in 1935. But for all the people who are seated today at the sidewalks in Buenos Aires and listening to Gardel's songs in their radios, that accident is irrelevant, because, they will tell you, ‘Today Gardel is singing better than yesterday, and tomorrow he'll sing better than today’. In one of his perennial hits, ‘My Beloved Buenos Aires’, Gardel sings: ‘The day I'll see you again/My beloved Buenos Aires,/Oblivion will end,/There will be no more pain.’ Omaramor is a fantasy on ‘My Beloved Buenos Aires’: the cello walks, melancholy at times and rough at others, over the harmonic progression of the song, as if the chords were the streets of the city. In the midst of this wandering the melody of the immortal song is unveiled. Omaramor is dedicated to Saville Ryan, ‘whose fire transforms the world.’”

The six Cello Suites of J.S. Bach are some of the most beloved music in the solo cello repertoire. With the single instrument, Bach is able to craft multilevel textures, wide stylistic variety, irresistible melodies, and musical range. Musicologist Wilfrid Mellers described the suites as “Monophonic music wherein a man has created a dance of God.” Pablo Casals’ recording of the suites revived and popularized them, and now they are performed frequently. Suite no. 3 in C major, like the others, is in the style of a dance suite. A variety of Baroque dances from the ambling Allemande and Minuet, to the pensive Sarabande, to the more upbeat Courante and Gigue, comprise the set. The prelude is profound in its simplicity: ascending and descending scales in C major set a welcoming, open tone, and straightforward harmonic sequences take the listener through a world of harmonic colors.

Carlos Chávez was a hugely successful 20th century Mexican composer whose career included a large presence in the United States and particularly New York City, where he became friends with the artist Rufino Tamayo. Much of his music includes folk elements from Latin America, including his String Quartet no. 3. The heartfelt Lento movement featured on this program features soaring lyricism and lush, dissonant harmonies. The movement begins with a lamenting melody from the viola that blends into patiently evolving chords.

Heitor Villa-Lobos wrote a grand total of 17 string quartets, one more than Beethoven, and they demonstrate the full range of the composer’s expressivity, stylistic variety, and technical mastery. They were clearly a favorite genre for Villa-Lobos, and his String Quartet no. 1 speaks to the composer’s ability to synthesize Latin American folk elements within a structured, classical form. Revised 30 years after the original composition year of 1915, the work contains an unusually large number of movements (six) that are mostly fleeting in duration. The second movement “Bringcadeira” (Joke), performed in this gallery, features pizzicato (plucking) from the strings and a vibrant, playful energy.

CONTEMPORARY GALLERY

An American composer teaching at the Longy School of Music in Cambridge, Massachusetts, John Howell Morrison writes in experimental ways that often challenge the listener’s sense of timbre and texture. Rising Blue is a work for violin and fixed electronic media that explores a variety of unorthodox sounds from the violin. About the work, Morrison writes: “Rising Blue marks my return to the world of electronic music after spending more than four years without significant access to a studio. The music of Rising Blue uses some very ancient procedures. In the first place, it partakes of the long-out-of-fashion accompanied sonata tradition. In certain works of Mozart and other classical composers, violin parts served more as obbligato accompaniment than as soloistic vehicles, and that describes somewhat the relationship between violin and tape here. Secondly, in the first large section each of the sound groups moves gradually to an individual cadence, much in the manner of vocal lines in polyphonic medieval and renaissance music. Every sound in Rising Blue was first produced on violin. The tape part incorporates a wide range of digital signal processing of those sounds, from virtually none at all to moderate alteration. The music is in two large movements, with an interlude and postlude of similar sonic content. The title of the work comes from the name I attached to the sound source of the postlude.”

John Adams is an American composer with countless awards, including multiple Grammys and a Pulitzer. His music is rooted in the style of minimalism, but also takes from other genres such as rock and blues. About his work Road Movies for violin and piano, Adams writes: “After years of studiously avoiding the chamber music format I have suddenly begun to compose for the medium in real earnest. (...) A breakthrough in melodic writing came about during the writing of The Death of Klinghoffer, an opera whose subject and mood required a whole new appraisal of my musical language. The title ‘Road Movies’ is total whimsy, probably suggested by the ‘groove’ in the piano part, all of which is required to be played in a ‘swing’ mode (second and fourth of every group of four notes are played slightly late). Movement I is a relaxed drive down a not unfamiliar road. Material is recirculated in a sequence of recalls that suggest a rondo form. Movement II is a simple meditation of several small motives. A solitary figure in an empty desert landscape. Movement III is for four wheel drives only, a big perpetual motion machine called ‘40% Swin’. On modern MIDI sequencers the desired amount of swing can be adjusted with almost ridiculous accuracy. 40% provides a giddy, bouncy ride, somewhere between an Ives ragtime and a long rideout by the Goodman Orchestra, circa 1939. It is very difficult for violin and piano to maintain over the seven-minute stretch, especially in the tricky cross-hand style of the piano part. Relax, and leave the driving to us.”

Aaron Jay Kernis is a Pulitzer Prize- and Grammy Award-winning American composer on the faculty of the Yale School of Music. Drawing from traditional tonal harmony and the history of the Western canon, Kernis’ complex and carefully formed music is accessible for its neo-romantic sensibilities, and relatable musical characters. Musica Celestis the second movement of his String Quartet written in 1990. About this particular movement, the composer himself writes: “Musica Celestis is inspired by the medieval conception of that phrase which refers to the singing of the angels in heaven in praise of God without end. ‘The office of singing pleases God if it is performed with an attentive mind, when in this way we imitate the choirs of angels who are said to sing the Lord’s praises without ceasing.’ (Aurelian of Réöme, translated by Barbara Newman) I don’t particularly believe in angels, but found this to be a potent image that has been reinforced by listening to a good deal of medieval music, especially the soaring work of Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179). This movement follows a simple, spacious melody and harmonic pattern through a number of variations (like a passacaglia) and modulations, and is framed by an introduction and coda.”

LATIN AMERICAN POPULAR ART GALLERY

Jessica Meyer is an American composer and violist living in New York City. An important part of her repertoire includes experimenting with a loop station, a device that allows you to immediately record and playback material during a live performance. With those materials, the performer can play “with” herself. About her work Source of Joy, Meyer writes: “When you think of the role the violist plays in typical classical repertoire, usually you think of lamenting melodies, throaty melodramatic outbursts, or patterns that help hold the ensemble together. After writing this piece, I realized that the sounds I used were quite the opposite from what is expected of a violist. Here we have high, soaring, groovy, and virtuosically powerful sounds. I wrote this piece after finally embracing the fact that I am indeed a composer, and thought that perhaps this was a fitting metaphor for life - because sometimes you have to go beyond what is expected of you to find your own source of joy...and it is never too late to do that.”

Carlos Gardel was a French-born Argentine singer, songwriter, composer and actor at the turn of the 20th century who played an extremely prominent role in the history of tango. Por una Cabeza, one of his most popular songs, features the impassioned, virtuosic tango style for which he was famous. The title is a Spanish horse-racing phrase meaning “by a head,” referring to a horse narrowly winning a race. The lyrics speak of a compulsive horse-track gambler who compares his addiction for horses with his attraction to women.

Argentine composer Alberto Ginastera, born in 1916 in Buenos Aires, is widely regarded as one of the most original South American composers of the twentieth century. His 1948 Milonga is inspired by one of the popular song forms of Argentina. Milongas, in syncopated duple meter, often have improvised lyrics, telling stories, most often tragic. Though it begins in a melancholy minor key, the piece ends in a brighter mood.

GREAT HALL

Heitor Villa-Lobos wrote a grand total of 17 string quartets, one more than Beethoven, and they demonstrate the full range of the composer’s expressivity, stylistic variety, and technical mastery. They were clearly a favorite genre for Villa-Lobos, and his String Quartet no. 1 speaks to the composer’s ability to synthesize Latin American folk elements within a structured, classical form. Revised 30 years after the original composition year of 1915, the work contains an unusually large number of movements (six) that are mostly fleeting in duration. The fifth movement, Melancolia, is a free-flowing expression of despair, passed between the instruments for passionate solos. Group moments of hopeful direction give way to reaching sighs and deep sorrow. By contrast, the sixth movement, Saltando Como Um Saci (Jumping like a Jumping Bean) is as a silly and light as the title describes. The movement references the structure of a fugue, popular among composers like Bach from the Baroque era, in which the instruments take their turn imitating the first subject or melody, and spiral into various musical episodes to create harmonic sequences through interesting keys. Drones in the cello, along with duets and various unisons, shake off the complicated fugue texture for something more grounded and jubilant.